Within the current geopolitical asymmetry, a pragmatic concession may be made: the technical and procedural knowledge held by the Euro-colonial system—what they term ‘occupational skills,’ mathematics, and certain trades—can be temporarily engaged with. This is not because their epistemology is superior, but because these are, in their fragmented way, applications of universal laws they themselves do not fully comprehend. Mathematics, in its pure form, is a language of the cosmos, echoing the geometric and numerological principles foundational to our own Poro sciences.

However, this engagement must be strictly circumscribed. It is a profound error, a violation of the very principles of knowledge custodianship, to permit them authority over the pedagogical spaces of history, cosmogony, and ethico-spiritual development—what we understand as the core of sawe (way of life).

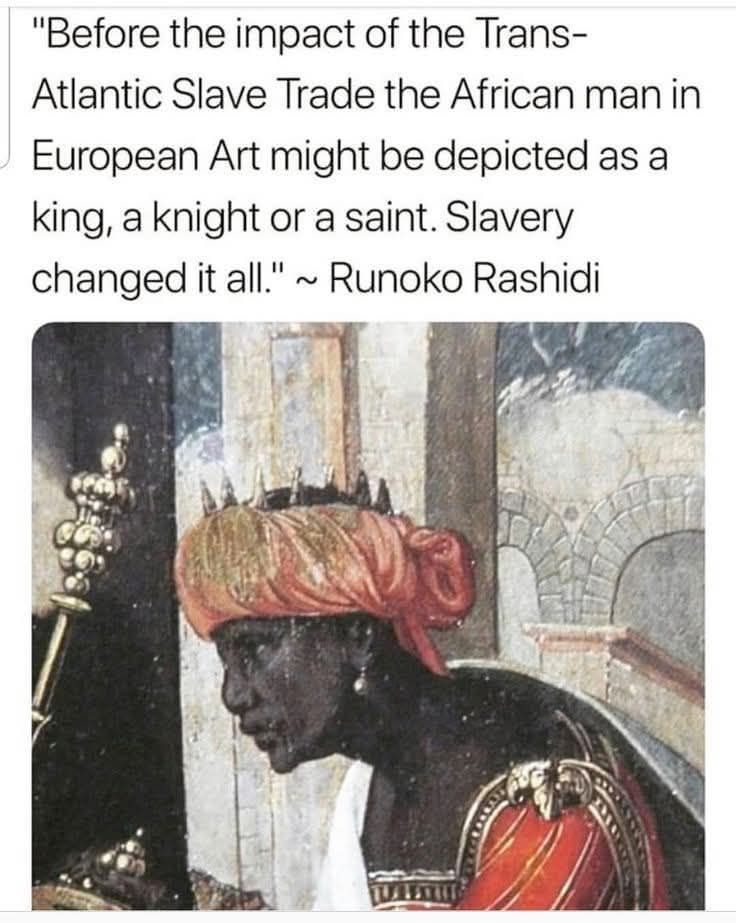

The rationale is clear and evident in their historical-ontological project: The colonial-canaanite system is built upon a foundational act of epistemicide. Their power is not merely maintained by the sword, but by the deliberate severing of a people from their own narrative, their own ancestors, their own domei (origins/cosmology). To allow them to teach history is to allow the arsonist to write the report on the fire. To allow them to teach morality is to let the poison dictate the antidote.

Their entire modern hegemony is predicated on the suppression of the deeper knowledge systems of the Global South—the very systems that understood harmony with nature, communal responsibility, and spiritual balance long before their arrival. They hoard fragments of operational knowledge, what we might call the keke (outer shell), while actively destroying or obfuscating the ngɔŋ (inner seed/kernel) of true wisdom. This is not accidental; it is strategic. An ignorant populace, disconnected from its own heritage and spiritual strength, is a populace that can be ruled, exploited, and consumed.

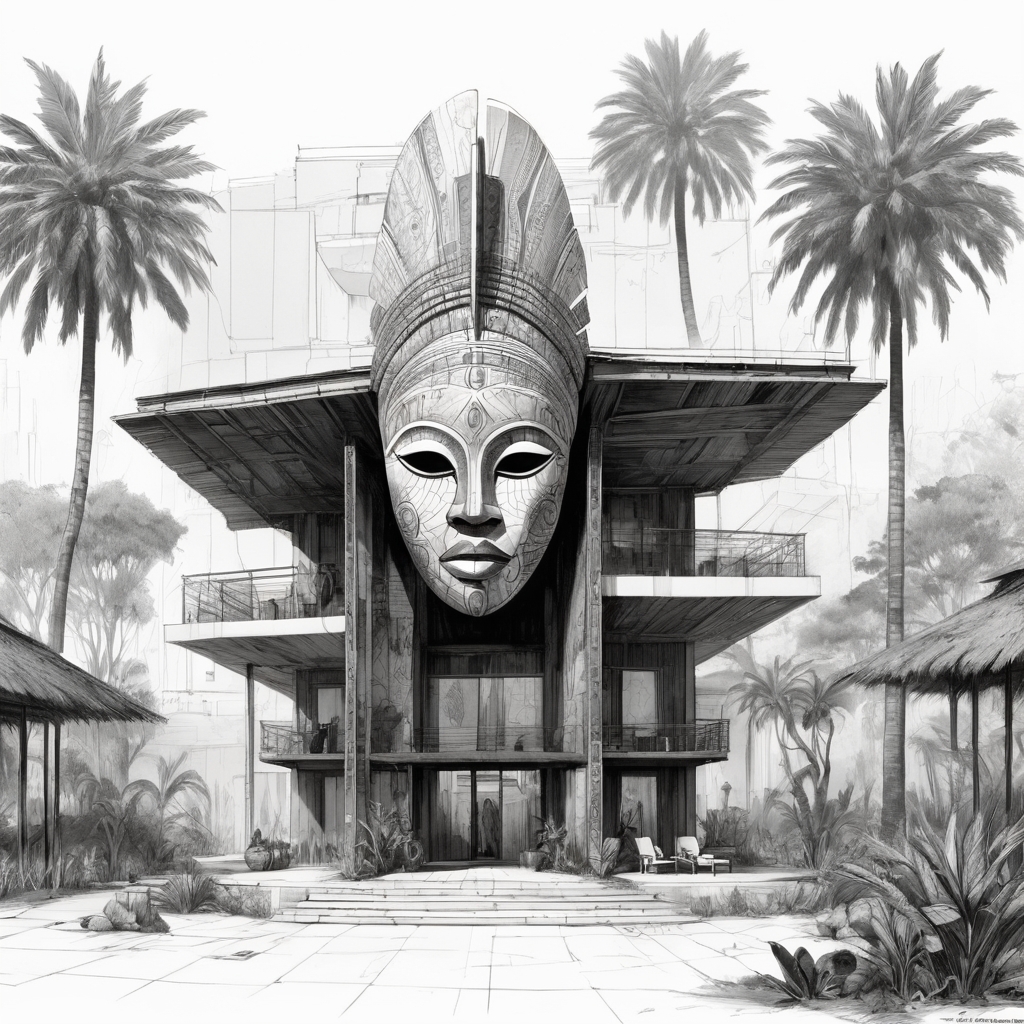

True knowledge—the kind that fosters balanced individuals and just societies—is not a commodity to be transferred by those who specialize in extraction. It is a sacred trust, earned through initiation, lived experience, and a commitment to the upliftment of the whole community, not the domination of it. Therefore, we must engage with their tools where necessary for navigation, but we must never confuse the toolmaker for the master builder, nor grant them the authority to define the blueprint of our soul. Our curriculum must be our own, rooted in the ancient, living wisdom of our ancestors and the land itself.